A Roomful of Computers: the Prescience of Lewis Fry Richardson

In a course I teach on geophysical fluid mechanics, I like show students a video depicting a year of weather on planet earth. The video looks down on a projected map of the world as viewed from space. Moisture rings the equator in a belt of clouds, riding ever westward on the trade winds. Over the Amazon jungle, clouds thicken and thin in a daily heartbeat. Fickle ribbons of tropical moisture—the famous atmospheric rivers—spin off into the mid-latitudes, periodically lashing places like California with drenching rain. The animation is utterly mesmerizing. Without reading the caption, it would be easy to miss the fact that this particular year of weather has never happened on planet earth. It is purely a simulation: an expression of the laws of heat and motion rendered in silico and mapped into color and motion.

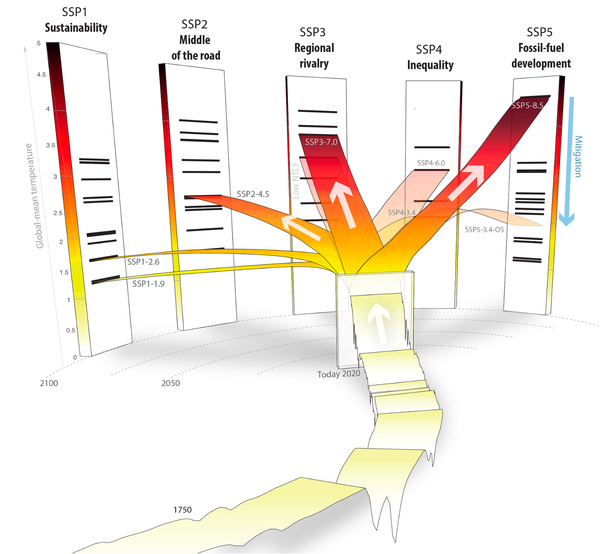

Weather simulations like this highlight one of the astonishing successes of 20th century science. Starting with a handful of fundamental equations, it’s possible to recreate in numbers the intricate and ever-changing fluid dance of the air and water around us. Although the phenomenon of deterministic chaos means that the precise details of the weather can’t be forecast very far out, the ability of models to reproduce patterns and long-term trends is remarkable. (To use the metaphor of an actual dance, we may not know precisely where the dancer’s left leg will be at any given moment in the future, but we can accurately predict the size and frequency of the various movements, sequences, and poses that will unfold during the performance.) This exquisite understanding of the forces of air, water, and heat that atmospheric models express turns out to be quite practical. It saves lives, for example, by providing advance warning of hurricanes and other tempests, and gives us a means of peering into the longer-term future of a warming planet.

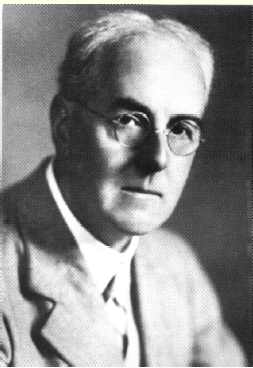

The groundwork for modern weather and climate modeling was laid by a British meteorologist named Lewis Fry Richardson (1881–1953). I had been dimly aware of Richardson’s work, and had (rather unfairly) imagined him as a brilliant but arrogant fellow, perhaps contemptuous of those whose mathematical rigor fell short of his own. But when I looked more deeply into Richardson’s life and times, I discovered that I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Born to a Quaker family in Durham, England, Lewis Richardson's interest in science led him first to Durham College of Science and later to Kings College Cambridge, where he graduated in 1903. Leaving Cambridge, Richardson alternated between positions in academia and industry. When World War I broke out, he was working for the British Meteorological Office, overseeing a weather observatory in Scotland. As a Quaker and a pacifist, Richardson declared himself a conscientious objector. In lieu of military service, he joined the Friends' Ambulance Unit, and spent the war years conveying wounded men rearward from the front lines. Returning to England after the armistice, Richardson found that his status as a conscientious objector effectively shut him out of university jobs. After briefly rejoining the Meteorological Office—he resigned again in 1919 when the Office was placed under the control of the Air Ministry—Richardson found work as head of the physics department at Westminster Training College, a teacher-education institution in London.

During the war, Richardson had filled his quieter hours working on a manuscript that outlined a bold new approach to the science of weather. He had seen how the laws of celestial mechanics had made the relative movements of the sun, moon, and stars beautifully predictable—an accomplishment that, among other things, helped revolutionize ocean navigation. Richardson’s dream was to do the same for the atmosphere. By 1916, he had completed a draft of his ideas and begun revising.

Then disaster struck. During the Battle of Champaign the manuscript was sent to the rear, where it vanished.

Luckily, as Richardson would recall, the lost manuscript was “rediscovered some months later under a heap of coal”. Four years after the war’s end, Richardson published his work under the title Weather Prediction by Numerical Process[i]. In one of the most remarkable passages, he wrote:

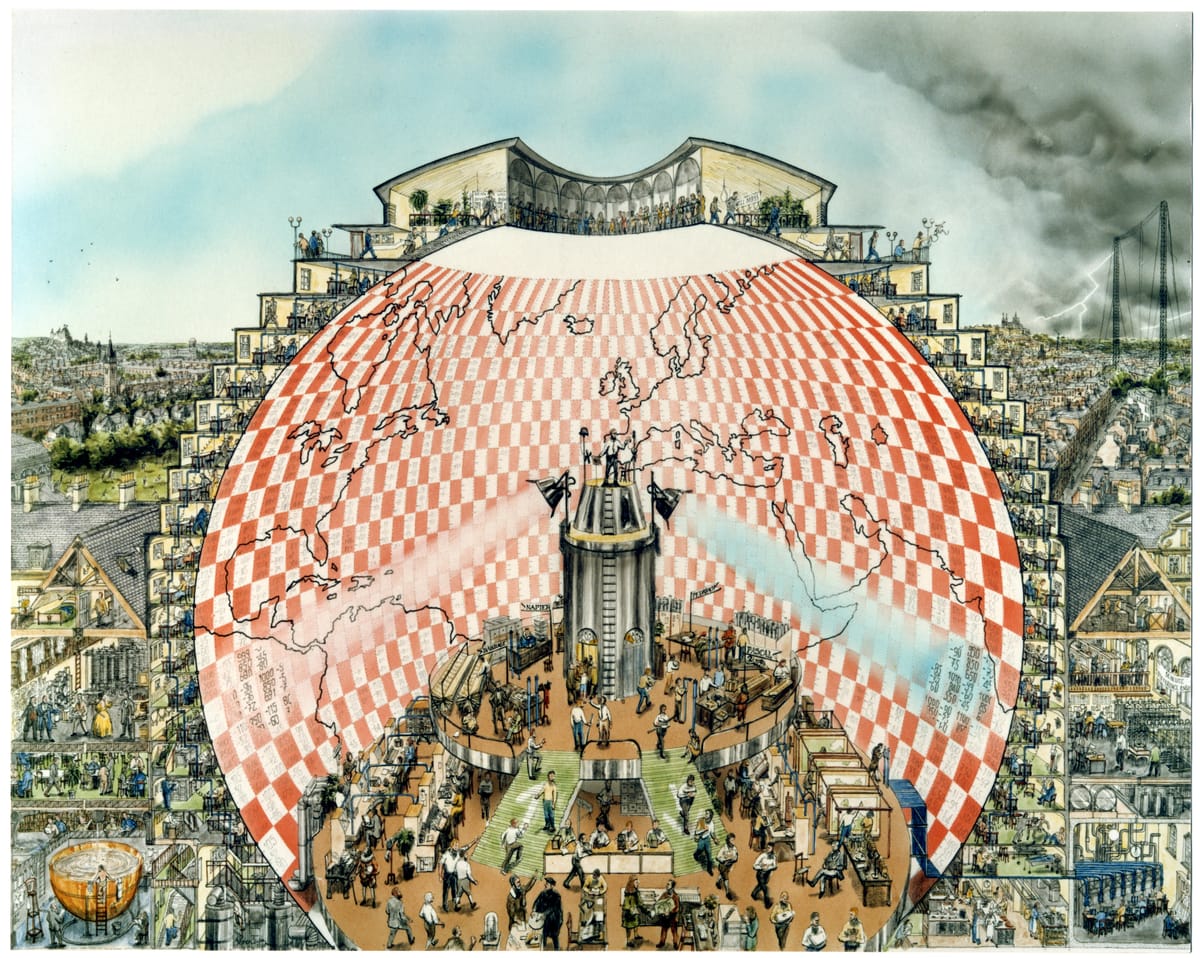

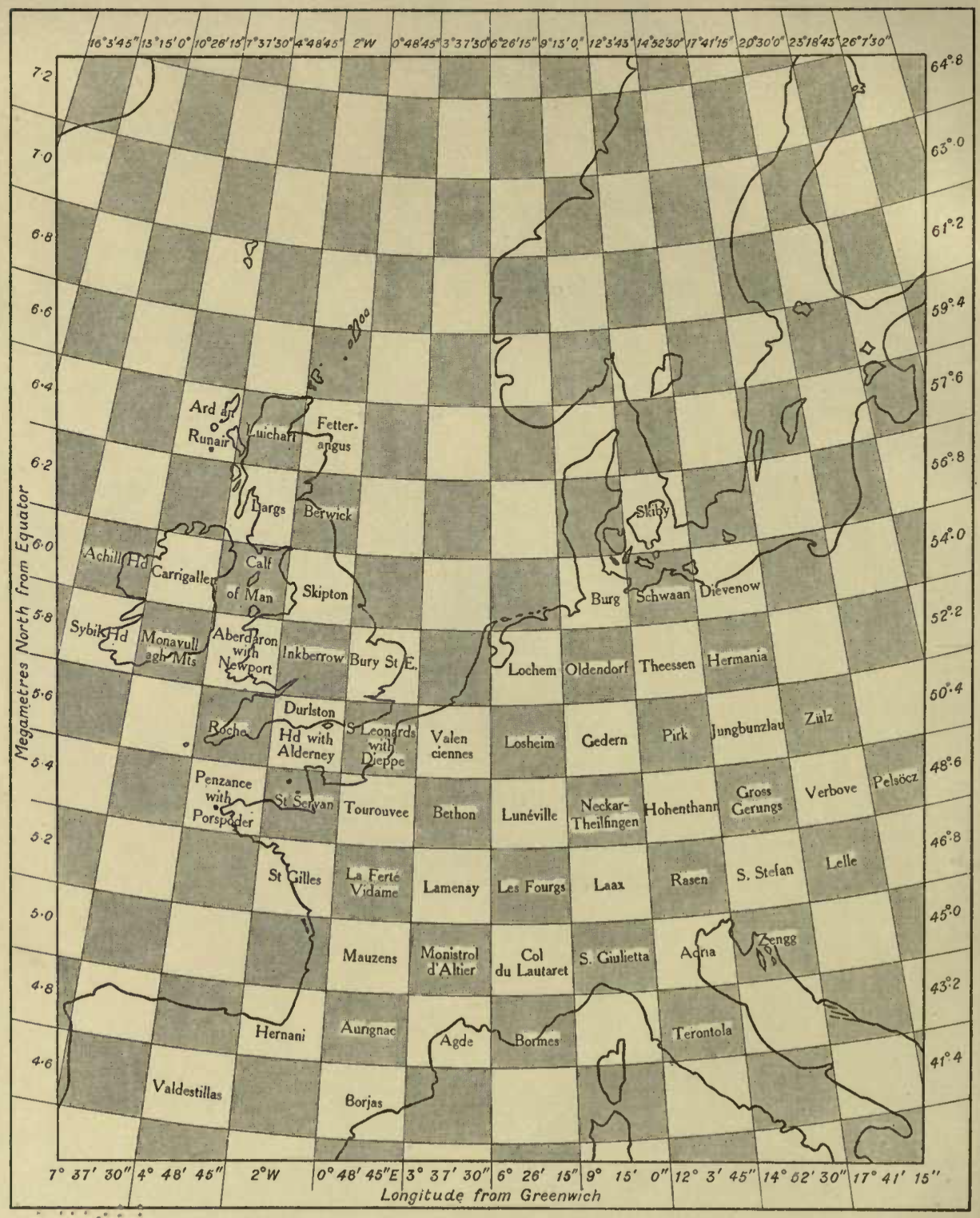

... may one play with a fantasy? Imagine a large hall like a theatre, except that the circles and galleries go right round through the space usually occupied by the stage. The walls of this chamber are painted to form a map of the globe. The ceiling represents the north polar regions, England is in the gallery, the tropics in the upper circle, Australia on the dress circle and the antarctic in the pit. A myriad of computers are at work upon the weather of the part of the map where each sits, but each computer attends only to one equation or part of an equation. ... From the floor of the pit a tall pillar rises to half the height of the hall. It carries a large pulpit on its top. In this sits the man in charge of the whole theatre ... he is like the conductor of an orchestra in which the instruments are slide-rules and calculating machines. But instead of waving a baton he turns a beam of rosy light upon any region that is running ahead of the rest, and a beam of blue light upon those who are behindhand.

The subject of all these calculations, of course, was the weather. The computers sitting in the chairs of this imaginary theatre, performing calculations and exchanging data, were not machines but people. In 1922, the word “computer” meant a job description: a person equipped with pencil, paper, and slide rule. In a sense, Richardson was describing the world’s first data center—one fed not by electricity but by tea and biscuits.

Lewis Fry Richardson’s dream of turning physical laws into forecasts would ultimately come true, and faster than he imagined. In 1950, a team of meteorologists in Maryland used ENIAC—an early digital computer—to produce the world’s first computational weather forecast. Richardson, then 68, was delighted by the news, describing the ENIAC experiment as “an enormous scientific advance”.

In the years following the publication of Weather Prediction by Numerical Process, Lewis Richardson turned his creative energy toward a variety of other topics. He is known, for example, as an early pioneer in what we now call fractal geometry, famously observing that the length of the coastline of Britain depends on the size of ruler one uses to measure it. He produced major works on the scientific analysis of war and conflict. And he was interested in the phenomenon of turbulence: the tendency of a fast-moving flow to break up into random-seeming eddies and whorls, which gives us babbling brooks and rattling airplanes.

When I cover the subject of turbulence in my geofluids course, I like to open with a poem that Richardson composed:

Big whorls have little whorls

Which feed on their velocity,

And little whorls have lesser whorls

And so on to viscosity.[ii]

From little whorls to playful fantasies, the work of Lewis Fry Richardson—scholar, pacifist, and visionary—is a lovely reminder of how science, at its best, thrives on wonder and imagination.

Notes:

[i] Richardson, L. F. (1922). Weather prediction by numerical process. Franklin Classics.

[ii] Richardson’s turbulence ditty was inspired by the mathematician Augustus De Morgan (1806–1871), whose poem Siphonaptera included the lines

Great fleas have little fleas upon their backs to bite 'em,

And little fleas have lesser fleas, and so ad infinitum.

De Morgan’s poem derived in turn from a section of Jonathan Swift’s 1733 On Poetry: A Rhapsody:

So, Nat’ralists observe, a Flea

Hath smaller Fleas that on him prey,

And these have smaller yet to bite 'em,

And so proceed ad infinitum:

History does not record whether Swift’s lines themselves derived from some prior work, which came from yet an earlier one, and so on down through deep time.