Anniversary of an eruption

June 15, 2025, marks the 34th anniversary of the eruption of Mount Pinatubo. In 1991, an unassuming peak fifty-four miles north of the Philippine capital of Manila blew its top, blasting more than a cubic mile of debris into the sky. Searing clouds of hot ash poured down its flanks, filling nearby valleys with hundreds of feet of pulverized rock and dust. A plume of hot ash rose more than twenty miles into the air. Pinatubo’s 1991 blast was the most powerful volcanic eruption on the planet in nearly eighty years.

Photos of the 1991 Pinatubo eruption show a huge dark gray cloud reaching high into the air above the volcano. So powerful was the blast that the cloud punched right through the lowest layer of the atmosphere. That puncture had global consequences.

Civilization exists in the bottom layer of the atmosphere, known as the troposphere. Depending on where you are and what season it is, the troposphere stretches anywhere from about five to nine miles above the ground. It’s the layer where weather plays out, and the home for most (not all) clouds. Commercial jets usually cruise at altitudes near the top of the troposphere, where the thinner air makes for better fuel efficiency. Dust injected into the troposphere—whether from a volcano, a dust storm, or pollution—tends to get washed out (or snowed out) fairly quickly.

Above the troposphere lies the stratosphere, home to the famous ozone layer, which partly shields us from the sun’s harmful ultraviolet rays. In 1991, Pinatubo’s roiling eruption cloud sent about fifteen million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. Once in the stratosphere, sulfur dioxide reacted with water to form a haze of so-called sulfate aerosols: tiny droplets mostly made of sulfuric acid. Sulfate aerosols tend to absorb and reflect sunlight, cooling the surface below. Pinatubo’s position in the tropics ensured that its aerosol shroud soon spread around the globe. The net result was a measurable planetary cooling, by around one degree Fahrenheit, that persisted for about two years before the haze finally washed out.

Pinatubo is just one example of a short-lived but world-spanning cooling event resulting from a large eruption in the tropics. For example, the 1815 eruption of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora cast such a chill on the northern hemisphere that 1816 became known in Europe and North America as the “year without a summer”.

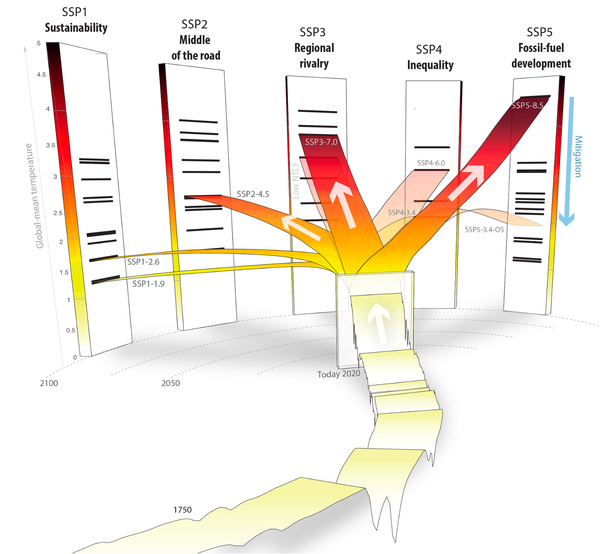

The transient cooling effect from Mount Pinatubo and other large very large eruptions has prompted the idea of intentionally injecting sulfate aerosols into the stratosphere as a means of countering global warming. This so-called “geoengineering” forms a key plot line in at least two novels: “The Ministry for the Future” by Kim Stanley Robinson and “Termination Shock” by Neal Stephenson (both are wonderful books that I highly recommend). But geoengineering with sulfate aerosols strikes me as a crazy idea. Even the word “engineering” itself is misleading: engineering implies a level of understanding and control that we are nowhere close to having for the earth system. In my view, we need to understand the system much better before it would make any sense to contemplate tinkering in this way with the planetary life-support system. A better course of action would be to invest aggressively in research to better understand the history and functioning of planet earth. (Unfortunately, US policy seems to be going in the opposite direction at the moment, despite the demonstrated fact that research investments more than pay for themselves; see, e.g., https://www.forbes.com/sites/johndrake/2025/05/19/trumps-nih-and-nsf-cuts-could-cost-the-us-economy-10-billion-annually/). As Mount Pinatubo reminds us, planet earth is a vast and amazing place, and we still have a lot to learn.