Anthropocene pilgrimage

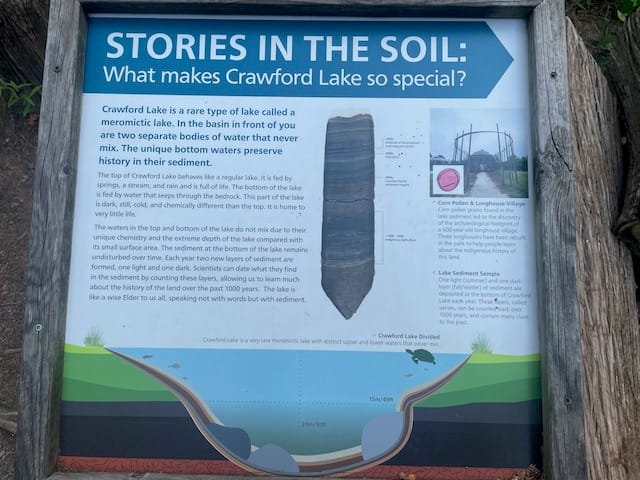

On a hot afternoon this past July I paid a visit to Crawford Lake, a tiny dot of water 30 miles southwest of Toronto. Only 300 m long and about half as wide, the lake fills an ancient sinkhole that formed when the roof of an underlying cave collapsed. In July 2023, Crawford Lake drew the attention of at least a small subset of the world when an eclectic group of scholars declared that its layers of mud contain the tell-tale signs of a new age.

The announcement came at a press conference held by the Anthropocene Working Group, or AWG. The AWG had been established in 2009, tasked with answering a big question: has human transformation of the natural world become so profound as to shift planet earth into a new geologic epoch? That notion, along with the name “Anthropocene”, had first been proposed by Paul Crutzen, a Dutch atmospheric chemist and winner of the Nobel prize for his work on the ozone hole. The name quickly caught on in the public imagination, and Anthropocene soon started showing up in book titles, magazines, academic journals, podcasts, and even a feature film. In a world that really has been transformed by humans, the concept resonated. But for all that people had reshaped the air, water, and soil, did it all really add up to an entirely new geologic time period?

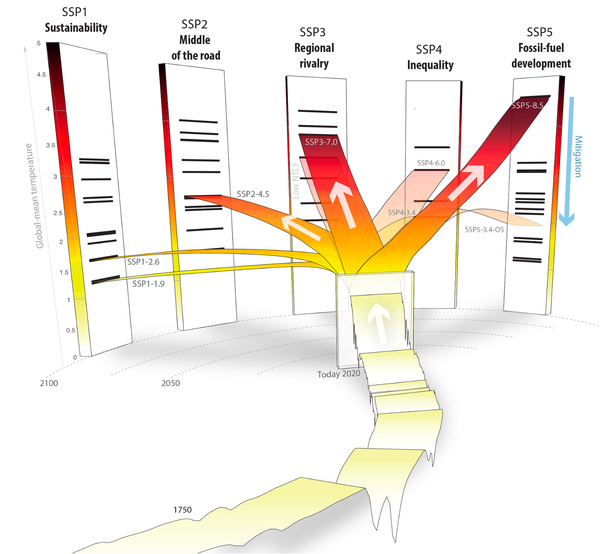

Based on 14 years of extensive research, AWG answered that question with a resounding “yes”. But changing the official geologic time scale is serious business, involving stringent rules and procedures. Among other things, there needs to be a designated place where the transition is recorded in layers of rock or sediment (or in rare cases, ice)—a so-called Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point, informally known as a “golden spike”.

AWG considered a dozen or so different golden spike candidates. The purpose of that press conference in 2023 was to announce the winner: Crawford Lake. Because of its unusual chemistry, the lake deposits annual varves—alternating drapes of light and dark mud—that make it possible to count the sediment layers back through time. AWG proposed that the Anthropocene epoch started, and the Holocene ended, in the year 1950. In sediment cores pulled up from the bottom of the lake, the layers from around 1950 contain tell-tale fingerprints of humanity. Most notably, they contain traces of the artificial radioactive element plutonium, the product of bomb testing in the Cold War era. The proposed golden spike was to be the 1950 sediment layer inside a core from Crawford Lake, which would be stored in a freezer to keep it intact and preserve its organic-rich mud.

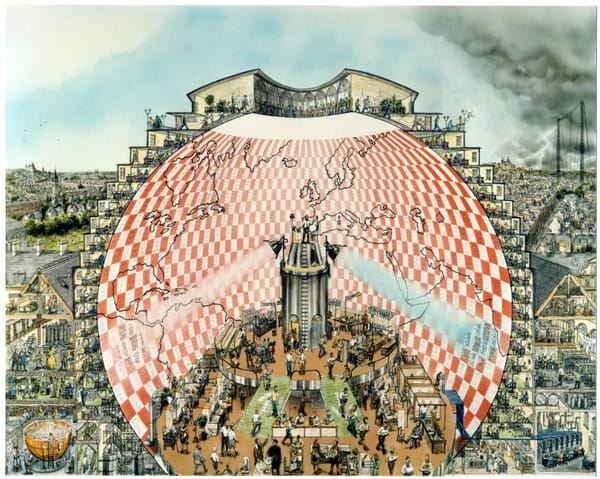

On my visit to Crawford, I found a placid water body surrounded hemlock and cedar forest. Birds flitted and sang: warblers and vireos, pewees and robins. Moss-cloaked blocks of dolomite ringed the shoreline, looking like ruins from an ancient civilization. On a hill above the lake stand a collection of reconstructed Iroquois longhouses—a memento to an ancient village whose existence had been revealed by traces of maize pollen in layers of lake mud dating back to the 14th century.

In March 2024, the International Commission on Stratigraphy—the body that adjudicates geologic time—voted down the proposed Anthropocene epoch. For the time being, therefore, we remain in the Holocene. Meanwhile, Crawford Lake quietly accumulates layers, year by year.