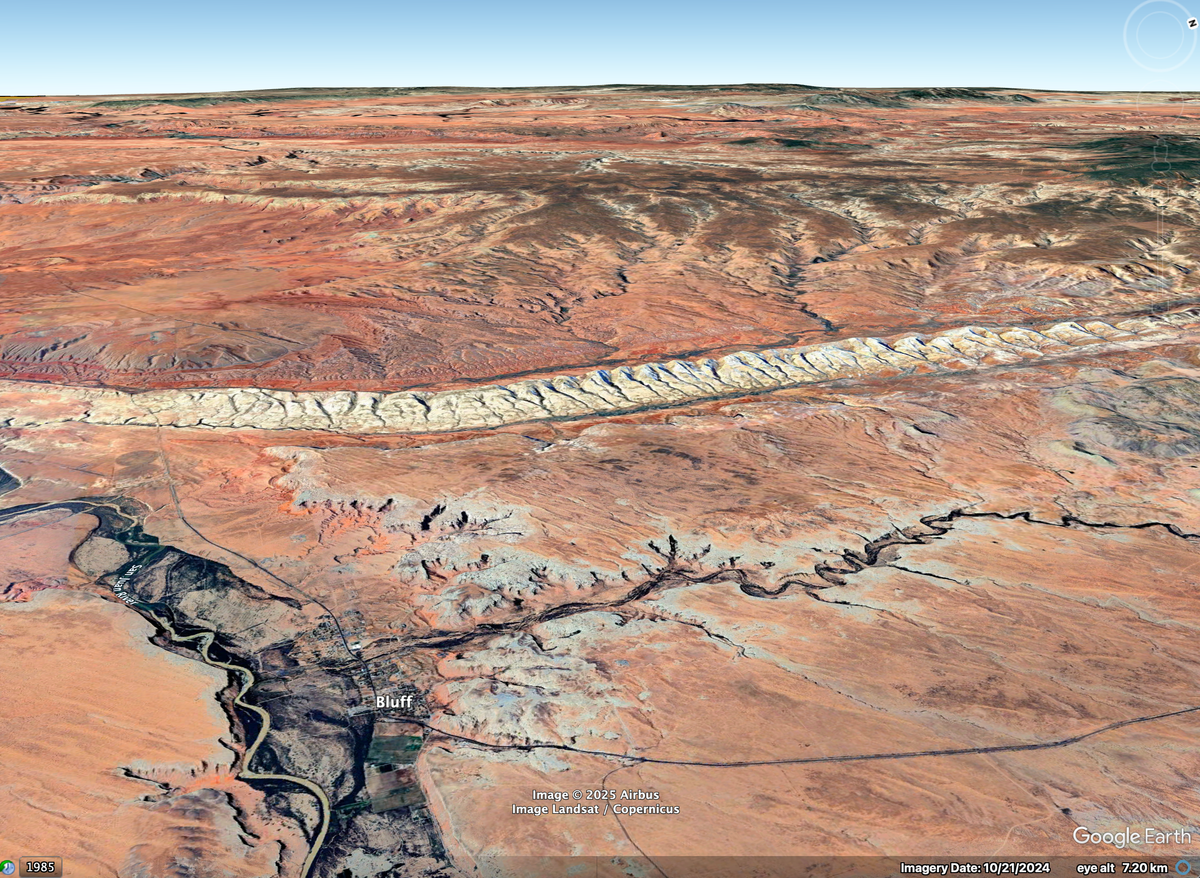

Comb Ridge: story of a landform

During the week of the Thanksgiving holiday, I had the opportunity to visit a remote part of southeastern Utah near the Bears Ears National Monument. A striking feature of this landscape is a long hogback called Comb Ridge, or Tséyik’áán in Navajo. The ridge is formed from layers of thick, hard sandstone that were bent upward during the building of the nearby Rocky Mountains. Its eastern side is sliced by steep canyons, their heads forming gaps along the crest of the ridge. The undulations from canyon to canyon vaguely resemble the teeth of a comb, hence the name. The western face forms a sheer cliff.

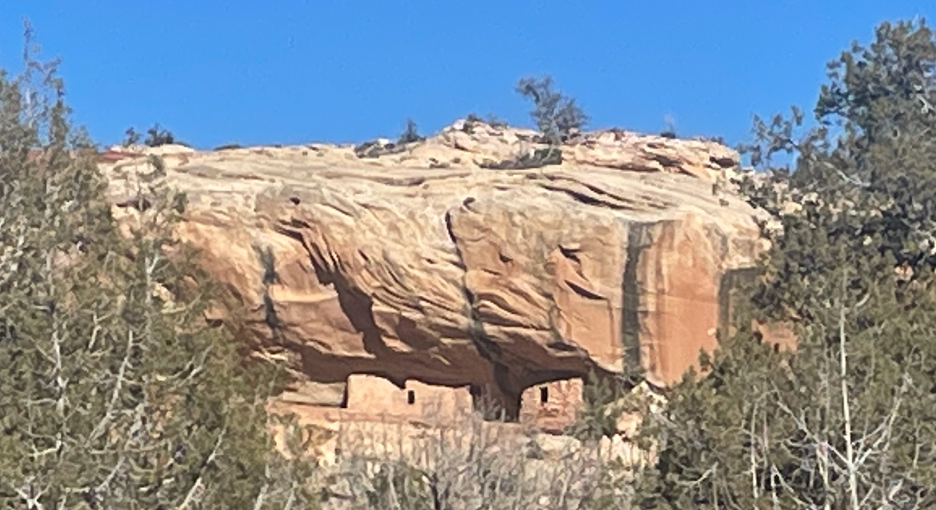

To the west of the ridge stands the lonely plateau of Cedar Mesa, its surface an open fuzz of pine and juniper trees. The mesa forms the top of the Permian-age Cedar Mesa sandstone: much older than the rocks that form Comb Ridge. Sinuous canyons slice through the sandstone. Here and there, abandoned cliff dwellings hug the canyon walls.

In addition to being a spectacular landform, Comb Ridge illustrates just how limited the English word “ancient” can be. Imagine being a grain of sand in one of those cliffs. Rewind the clock 280 million years. You first meet what will become your long-term neighbors as you are blown around together in a field of desert dunes: the kind of thing that will one day be called an erg. Call it the Cedar Mesa Erg. Moment to moment, the wind-whipped sands cascade down the faces of a thousand dunes, each avalanche buried by the next, writing a train of sloping layers like tilted books on a shelf. Year by year, you and the dunes around you get buried; water percolates around you, its discarded minerals gluing you and several billion friends together in a ribbon of stone.

You pass your 35 millionth birthday. Somewhere up at the surface, drama is happening. Most of life on earth perishes; then, what’s left of it goes on. By your 100 millionth birthday, dinosaurs are hunting and foraging in the sand and mud of a river somewhere above you. One by one they live their lives, leave their bones in the mud, and are buried. Their stony grave becomes the Kayenta Formation, stained dark red by the rusting groundwaters.

The Kayenta’s dinosaurs rest in their rocky grave for over 100 million more years. Below them you sleep too. Then something wakes you up. A shaking, a bending, and a hoisting. A tectonic shove from beyond and below. From the north and east come the distant vibrations of lurching mountains. Here in your chunk of land, the carpet wrinkles: rising on the west, sinking on the east, kinking in between. The Kayenta layer is now sharply bent. This bending is ancient too.

Now, a rising and a scraping and a clawing. Rivers drag their rocks, cutting; water soaks the stone back into sand. An unpeeling. Somewhere on the land above, sunlight beams on a sliver of red rock. Flood by flood, the dinosaur’s gravestone is etched open, its high parts carried off to the sea, and its low parts still buried for now. In between, the kink becomes a ridge. A few miles to the west, daylight blinds you (or would if you had eyes) as a slab of canyon rock splits off, exposing you on the fresh cliff face.

People find the ridge. It becomes a barrier, and a meeting point. They carve footholds in the steep western face. At the top, they paint the rock. In the 13th century, drought strikes, conflict waxes. People build houses along your cliff, for defense and concealment.

All of these versions of “ancient” come together at Comb Ridge. On an usually warm, calm day in November, I hiked up one of its canyons, reaching a vista point at the rim where petroglyphs decorate the sandstone walls. In the valley to the west, the tectonic event that built Monument Upwarp raised older layers from the Permian and Triassic Periods. Despite this, the land itself forms a valley: the result of erosion hollowing out the soft rocks, leaving the younger and tougher sandstones to form a jagged ridge.

At this point I should confess something: I’m a geomorphologist. That’s the branch of science that deals with landforms and their changes in time, whether they be swift or slow. So on the long ride home I couldn’t help pondering Comb Ridge. Fortunately, my traveling companion likes to drive, so I was free to explore, via laptop and computer code, how the ridge formed. The image below illustrates a simulation of one possibility (see also this animation).

Output from an animation showing simulated landscape evolution with a buried hard layer (colored off white) between two more erodible units. View is looking to the north.

The story starts with three buried layers, one representing the hard Wingate, Kayenta, and Navajo sandstones that make up the ridge; one for the soft Triassic age sediments below them; and one for the soft Jurassic age sediments above. When the simulation begin, they have already been bent into a stretched-out and curvy Z-shape, [1] somewhat like this:

‘ ‘ ‘ \ , , ,

In other words, you (as the sand grain) have already been long buried, and the rocks around you already bent by tectonics, by the time our simulation starts. To represent regional erosion, the right-hand edges of the domain gradually lowers, as if cut by a large river just out of view. Digital water rains across the gridded terrain, following the easiest path downhill and eroding the land as it goes. The uplifted part of the hard layer gets exposed first, forming a high plateau drained by eastward-flowing streams. The streams break through into the soft layers below and the plateau’s cap is gradually worn away, leaving only the kinked part, which juts up from below at a steep angle. For a while, the east-flowing streams cut canyons through this hard layer. Then, one by one, they are captured, leaving behind a row of wind gaps along the ridge: the cavities between the teeth of the comb. Despite its simplifications and abstractions, the simulation seems to capture the essence of how Comb Ridge might have formed.

Simulations like this allow us to compress time, to speed up weather and water and wear to something that can fit inside a human mind. Still, a visit to a landform like Comb Ridge—a place that was ancient before the ancients arrived—provides a delicious reminder of the spaciousness of time.

Notes and acknowledgments

[1] In case you’re curious, I made this shape with a hyberbolic tangent function.

Thank you to Alex and Judy for introducing me to Comb Ridge.