Scientists in times of turmoil

In the course of a project I’ve been working on, I’ve learned a bit about the life and times of various earth scientists of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries. It's been interesting to see how these scholars dealt with living in tumultuous times.

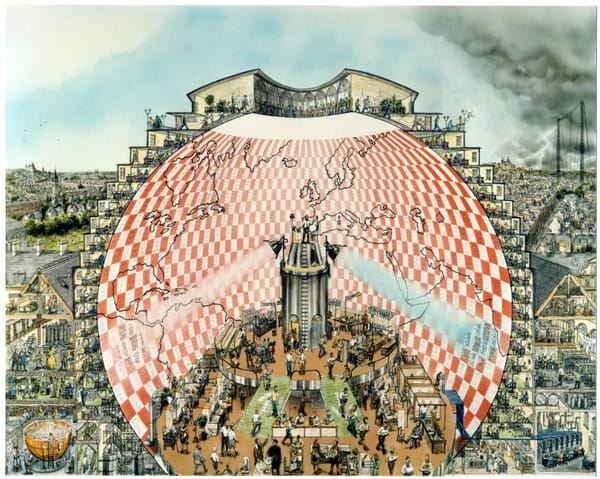

Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), a Prussian, managed to live and work in Paris much of his life despite the turmoil of the Napoleonic wars (though the King of Prussia later ordered him back to Berlin). He even managed to sustain Spanish government funding for a while, despite his critique of Spain's colonial rule. (For more on von Humboldt's remarkable life, I highly recommend Andrea Wulf's The Invention of Nature.)

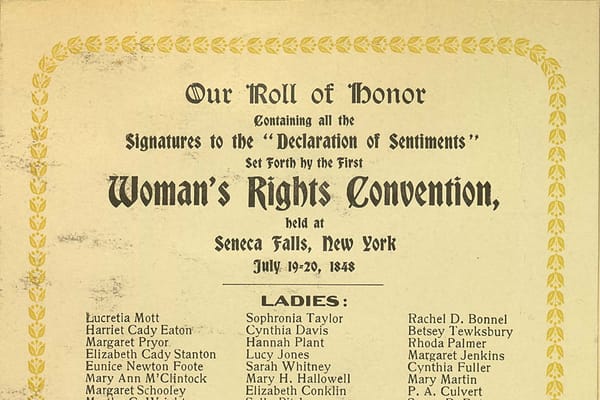

In the US, Major John Wesley Powell (1834–1902) lost an arm in the Civil War. His contemporary, the inventor and scientist Eunice Newton Foote (1819–1888), was also an abolitionist and a womens’ rights campaigner; she lived to see victory in just one of those causes.

In Britain, the Quaker scientist Lewis Fry Richardson (1881–1953) refused to fight in World War I, and instead served in the Friends Ambulance Corps. He wrote one of his major works (and nearly lost it) while on the front lines.

In Serbia, Milutin Milankovitch (1879–1958) was arrested by the Austro-Hungarian empire while on his honeymoon in 1914. But he was allowed to live in Budapest and do research at the library. Later, when the next world war broke out, his opus on orbital causes of ice ages was nearly lost in the 1941 bombing of Belgrade.

The climatologist Mikhael Budyko (1920–2001) was born in Petrograd, spent most of his career in Leningrad, and died in St. Petersburg—all in the same city, while managing to produce major new insights into the climate system.

Norman Phillips (1923–2019), an American meteorologist who wrote the first computer model of general circulation of the atmosphere, got into the subject through wartime service in the Army Air Corps. So too did Edward Lorenz (1917–2008), the father of chaos theory, who switched his PhD topic from math to meteorology after the war. Charles Keeling (1928–2005), the discoverer of the Keeling CO2 curve, graduated from high school in 1945. To avoid being drafted in those last few months of the war, he went straight into a chemistry program even though, as he later admitted, he wasn't especially interested in chemistry.

On the other side of the Pacific, an adolescent named Syukuro Manabe (born 1931) watched US planes fly overhead on their way to bomb Japan's big cities. After the war, he emigrated to the US to begin a lifelong career at what's now NOAA. In 1967, he published the first computer model of the greenhouse effect, and in 2021 he won the Nobel Prize for his contributions to climate modeling.

As painful as it is to watch a free and prosperous society coming apart at the seams, I find it somehow comforting to know that for hundreds of years people of good will have managed to continue this multi-generational project of art, literature, music, and science: trying to figure out how the world works, and exploring and expressing what it means to be human.