The Wizard of Seneca Falls

I’m enchanted by waterfalls, and not just for the obvious reasons. To a geologist, a waterfall is a slow-motion wave in solid rock. Occasionally you find waterfalls that are stationary, pinned in place by some hard piece of geology: an ancient dike of frozen lava, say, or a vertical wall of tough quartzite inside a sandwich of mud. Most of the time, though, waterfalls are traveling waves. With every flood, the thundering water plucks and grinds a little more off the rocky face, driving it upstream step by tiny step. Once in a while, a large chunk breaks loose, tumbling downstream, opening up a gap that re-draws the foaming current. A waterfalls speaks of transience: a kick from some disturbed past birthing a hydraulic fury that drives upstream like a slowly burning fuse, leaving behind a trail of polished boulders to mark its slow passage.

So I was excited to visit the town of Seneca Falls, New York. The town hugs the Seneca River, which drains (you guessed it) Seneca Lake. Unfortunately I was a century or so too late. The falls were once a series of natural rapids that dropped the river down about 40 feet. By 1915, canal builders had entombed the cascade in a dam-and-lock complex, which now impounds a water body called Van Cleef Lake. For the time being, Seneca’s rocky wave has been arrested in concrete.

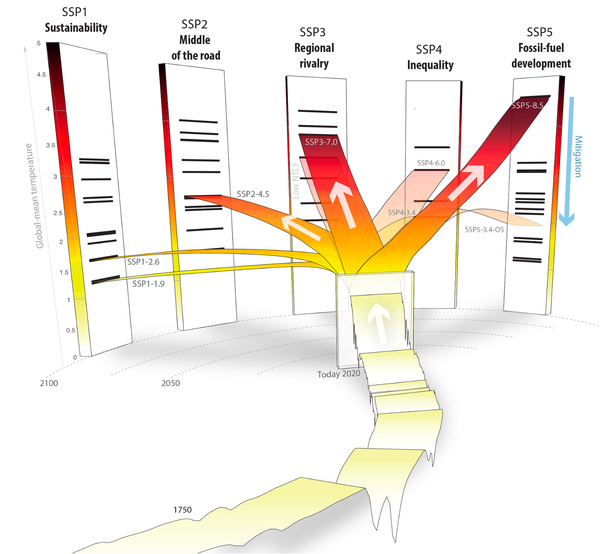

Fortunately, Seneca Falls has other delights to offer. I first heard of the place while reading about the life and times of Eunice Newton Foote, who lived there in the mid 1800s. Foote was, among other things, an inventor and a scientist. She had multiple patents to her name: a thermostatically controlled stove (1842), a shoe and boot insert of vulcanized rubber (1860), a paper-making machine (1864), a strapless skate (1868). My interest, though, was in her contribution to earth science. In 1856 Eunice Newton Foote conducted experiments on the absorption of sunlight by various gases. Among her subjects was carbonic acid gas, nowadays known as carbon dioxide or CO2. Foote found that CO2 absorbs radiant energy. Because of the nature of her apparatus—gas-filled glass jars exposed to sunlight—Foote was not able to identify the underlying mechanism (five years later, experiments by John Tyndall in Britain revealed that CO2 strongly absorbs infrared radiation). But she was farsighted enough to understand the implications of her findings. “An atmosphere of that gas,” she wrote, “would give to our earth a high temperature; and if as some suppose, at one period of its history the air had mixed with it a larger proportion than at present, an increased temperature … must have necessarily resulted.” In other words, Eunice Newton Foote was the first person to recognize the powerful role that CO2 plays in controlling earth’s surface temperature.

Not that she got much credit for it at the time. Her results were presented at the 1856 meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, but not by Eunice Foote. Instead, a gentleman named Joseph Henry presented on Foote’s behalf. Henry remarked to the audience that “Science was of no country and of no sex. The sphere of woman embraces not only the beautiful and the useful, but the true.” History does not record whether Foote was present, and if so, whether she cringed at this. In any case, her brief published report seems to have been ignored for the next century or so, overshadowed by Tyndall’s more sophisticated experiments.

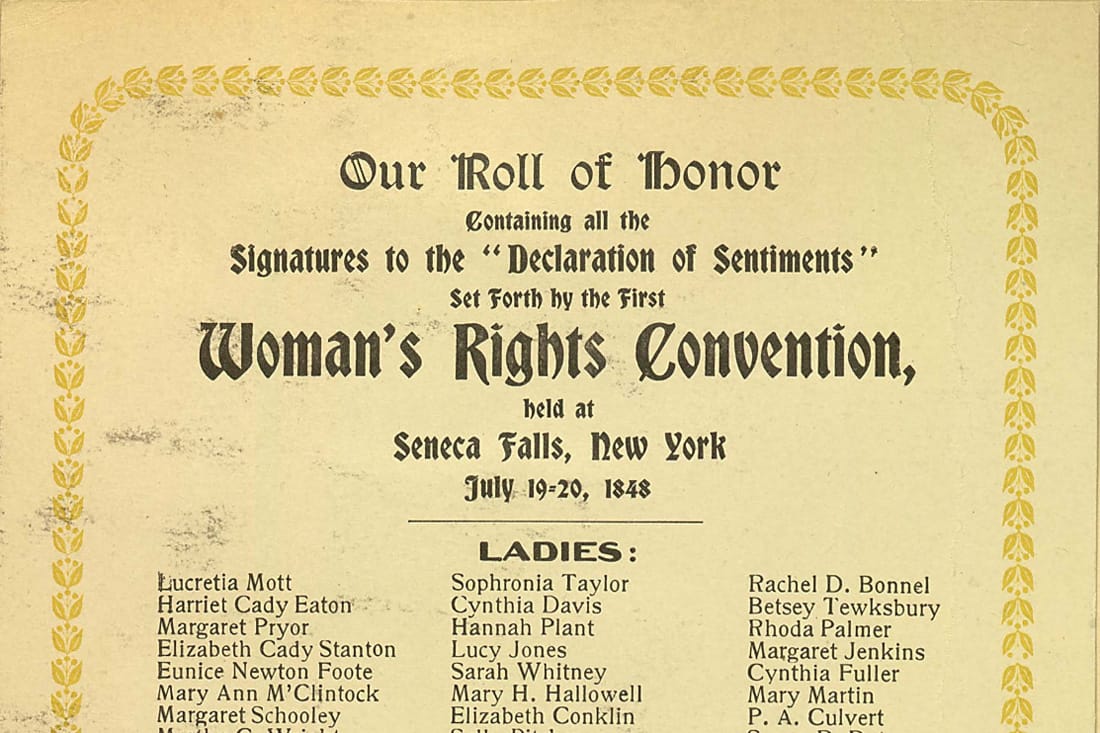

Meanwhile, Eunice Newton Foote must have been busy. Among other things, Seneca Falls in the mid-1800s was the epicenter of the American women’s rights movement, and Foote was in the thick of it. She was closely involved in the first-ever conference dedicated women’s rights: the Seneca Falls Convention, held in July 1848 at the town’s Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. Today, in honor of that event, Seneca Falls is home to the Women’s Rights National Historical Park.

I arrived in Seneca Falls on a hot July day and parked on the main street. Across the road was a row of tents, of the sort you see at craft fairs and farmers markets. A large banner on one tent read “Feminist Lemonade.” I walked two blocks toward the National Historical Park, where a Visitors Center stands next to the Chapel. A crowd was gathered around the Chapel entrance, including a group of girl scouts who giggled as they tried to wedge themselves into a tiny patch of shade from a sidewalk tree. By sheer dumb luck, I had arrived at the exact day, time, and place of the annual commemoration of the Seneca Convention.

The chapel doors opened, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton herself (or rather, an actress portraying Stanton) emerged to greet us and usher us into the chapel. Someone mentioned that the actress was actually Stanton’s great-great-granddaughter. Elizabeth Cady Stanton was assisted by none other than Frederick Douglas, with his memorable shock of curly gray hair. We filed into the refreshingly cool and austere space, and took seats on the wooden pews. Above us, where the chapel’s upper gallery had once existed, hanging paintings depicted the gallery as it might have appeared on those two days in 1848: women, men, and children in 1840s garb; some scowling, some thrilled, some quietly curious.

Frederick Douglas stood to welcome us and declare his enthusiastic support for the cause, just as the real Frederick Douglas had done at the Convention. Then Stanton took the lectern, and read from the Convention’s Declaration of Sentiments:

“When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.”

The Declaration concluded with a note of determination:

“In entering upon the great work before us, we anticipate no small amount of misconception, misrepresentation, and ridicule; but we shall use every instrumentality within our power to effect our object. We shall employ agents, circulate tracts, petition the State and national Legislatures, and endeavor to enlist the pulpit and the press in our behalf. We hope this Convention will be followed by a series of Conventions, embracing every part of the country.”

The written declaration has a long list of signatures. Eunice Newton Foote’s appears near the top, just below Stanton’s name.

Eunice died in 1888, more than three decades before ratification of the 19th amendment. What if she had been able to time-travel, Lazarus-like, through the 20th century and into the 21st? What would she make of today’s world? Undoubtedly she’d be pleased to see progress on human rights; probably she’d be disappointed at the slow pace. And what of her hunch about carbonic acid gas? I imagine Eunice being thrilled to learn that her intuition was spot on, that in fact the absorption of radiant energy by CO2 now forms a central pillar of climate science.

And what would she make of modern efforts to discredit climate science? I imagine her smiling ruefully and remarking, in her mid-19th century dialect, that she’s seen plenty of that sort of thing before.

A load of cement can bury a waterfall, stalling its progress for a while. But the river's power persists, and in the long run, waterfalls break through.